Searching for Global Community, Part 1

From the dial-up BBS to social media, something has gone wrong with how we socialize on the internet.

A Quick Introduction

One of my reasons for starting this blog was a hunger to build a little more digital community with all of the interesting people I've connected with over the years. I've always had a strong desire to be part of a global community. The further the places I go, the more interesting the people, ideas, and viewpoints I encounter – and it's addicting. That desire has led me to push my career in directions that naturally get me out into the world, and as a result I've been very fortunate to get to know and work with some really interesting people from a lot of places.

But somehow, despite being instantly "connected" with all of those people around the world on various chat and social apps, it never quite feels like real digital community. After 30 years of internet technology advancement, something important feels missing on today's standard form of connecting with people online: social media. Maybe you've also felt the pit in your stomach as you scroll through your feeds and tap like.

I've long found this frustrating because I have experienced real community online in the early days of the public internet (and pre-internet) when it was first possible to be instantly and digitally "connected". What have we lost, and how did we end up here?

In trying to answer those questions, I've discovered that the difficulty in finding satisfying community online is just one symptom of a much larger and quite profound change in human society that been accelerating across the last 30 years since we first start moving online. That change is so large-scale that it's extremely difficult to see in whole, even through the symptoms we feel in many parts of our lives are very familiar. As just a single example, we live in a time when we can watch first-hand as real geopolitics are conducted between the most powerful nations on earth in public over Twitter; that sure wasn't the case even 10 years ago, and it would have been unthinkable 20 years ago. I think many of us have the sense, with increasing panic, that the world has been knocked out of balance in some way, and it at least has something to do with social media.

I want to explore that big society shift. But to paint some background first, I want to tell you about the strange experience of growing up while making the leap from a fully analog world into some of the very earliest and vibrant forms of digital community and how that early promise has been lost in the world of social media today.

(If you want to skip the slightly self-indulgent GenX geek nostalgia, you might consider skipping straight to part 2. I won’t be mad.)

The End of a Disconnected World

I was born in 1977, the year of the Apple ][ and the TRS-80 and right when the first mainframes were being connected via TCP/IP to become the embryonic internet. Those two technological advancements – the personal computer and the internet – would mature and come together in the 1990s, exponentially increasing each other's power to create the beginnings of a world-remaking revolution.

Those years of the 80s leading up to a revolution were, in retrospect, the last years of a disconnected world. It's a difficult mindset to recall now, but prior to the devices and platforms that would remake our lives in the 90s and beyond, our whole lives in the 80s were largely defined by the contents of a bubble of physical territory that we could easily walk or drive to.

Of course we weren't completely cut off from the world. The technology available in the 80s could bring you information from outside your bubble – but slowly and from a limited set of broadcasters and publishers with access to the mechanisms of mass media. You had to tune into your local evening news broadcast, get delivery of a daily newspaper, borrow a book from the library, or visit the local auto club for a map. You were aware of the world out there, but it still felt distant.

Your actual experience of living was inherently local. Specifically, your community – the people you talked to, worked with, shared with, sought approval from, and more – could realistically only be drawn from the people in your walkable/drivable bubble that you could meet and spend time with in person.

But didn't we still have options in the world of the 1980s for 2-way communication outside our bubble?

Sure, you could send a letter or (expensively) make a call to somebody on the other side of the country or world. But that's just correspondence, a single conversation. You could have a group of people living in different cities united by a common interest or family ties, but the only way they were held together as a community was to meet up somewhere in person once in a while. Those in-person gatherings were where individuals became known members and engaged in the real business of sharing, discussing, arguing, contributing, and competing. Afterward you all went home to your local communities and promised to "stay in touch" until the next time you got together to take the community out of suspended animation.

Discovering Pre-internet Digital Community

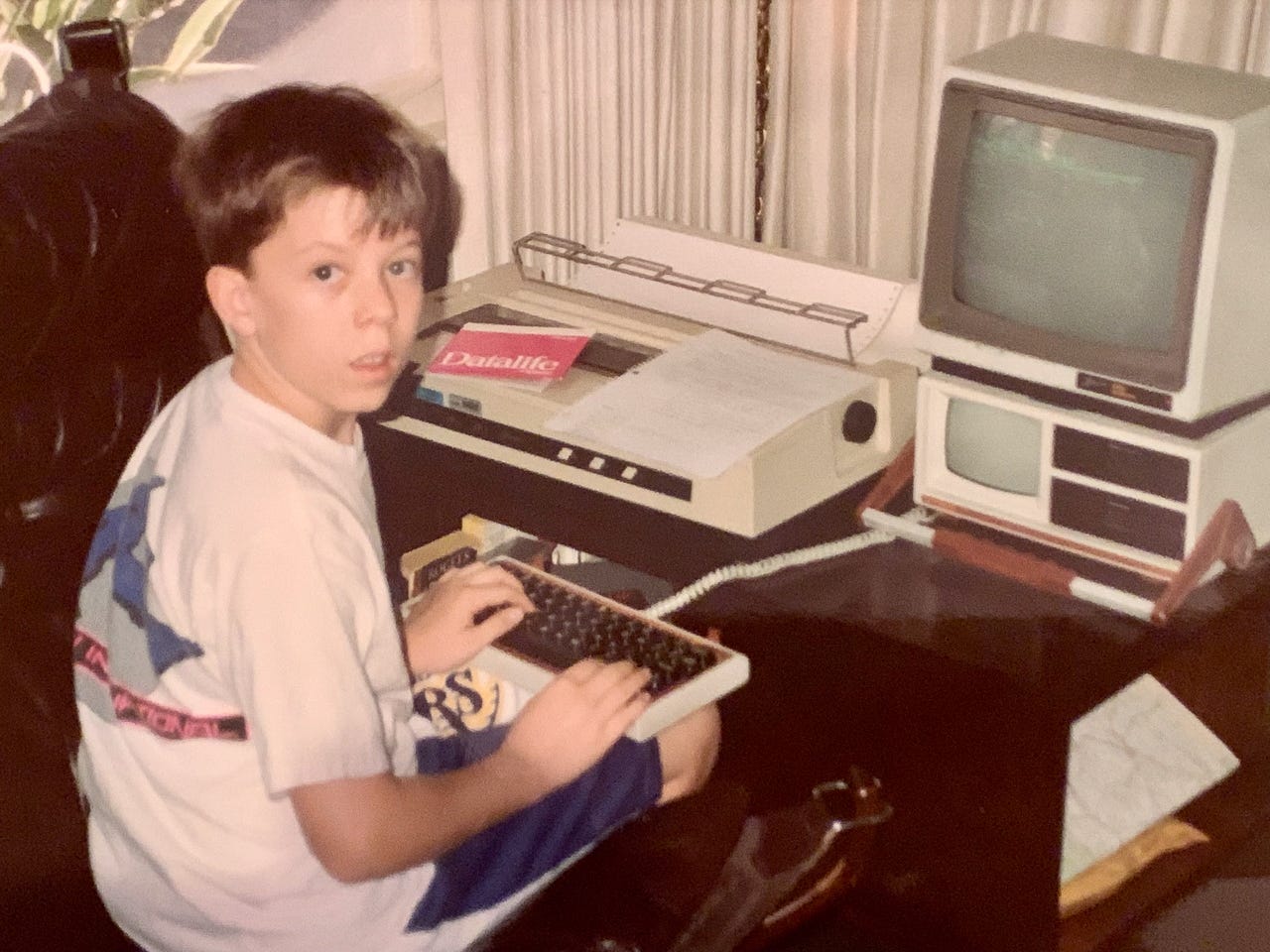

Within that world, as a kid and a congenital geek, computers were exciting. Fortunately I had the extreme good luck to grow up in Southern California around JPL engineers and scientists, and with access to early personal computing hardware. When I had to choose summer classes, my finger slid straight to computer programming (LOGO and BASIC). A government-issued "portable" PC came home with my dad at one point and was instantly annexed by me to write simple programs, tap out ASCII art, and play text games like ZORK.

When the movie WarGames came out in 1983 and Matthew Broderick connected his computer over a phone line using a modem (!!) to a government system (with an AI no less!), nerd minds blew. I may have written a script to simulate me hacking into a DoD mainframe and launching Global Thermonuclear War.

Nothing felt more crackling with potential to me than the idea of connecting my computer to other computers used by other people in distant places.

Consumer modems first became available years before the internet became widely accessible. The main use was dialing into private corporate systems, but quickly people created something else you could dial into: bulletin-board systems (or BBS's). So of course as soon as one friend's dad brought home a modem for work, he managed to get his hands on a list of BBS phone numbers around LA and we started dialing. And what did we find?

Digital communities. And wild ones.

Each BBS was the home for a group of people who used "handles" instead of real names, but they were known within their community by what they said and created and shared. They posted ideas and rants to a common message board. They sent private messages to each other. As a group, they created a shared repository of stories and art and demo code (and, er, less noble things) often created by the members themselves.

They had bitter arguments, they found friendships, they formed cliques and collectives, and they fed off each other's creativity and competed with each other. Anyone could dial in to a BBS fresh, but a new user often had to earn acceptance into the community – either by raw contributions to the commons, or sometimes by demonstrating they were a reasonably interesting person to talk to, not just a leech.

BBSes were still largely local, however. They drew their denizens from within local borders drawn by the AT&T company because nobody wanted to pay ludicrous long-distance fees for their modem to stay connected for hours. But for a teenage geek in the early 90s, you could suddenly find (or even create) a community of your people not just from your school, but from all of the schools of your area code (hundreds, if you were in Los Angeles at the time like me). And you were more likely to find a lot more of your people there because kids who were drawn to dialing in to BBS's tended to have some, er, commonalities of personality and interests (which might not make them so popular at their respective schools).

The revelatory impact of experiencing this new form of community is hard to explain.

The Importance of Community

Community is an incredibly powerful thing; the desire for it seems wired into us at a genetic level. We have a need to belong to groups where we are known for who we are and what we've achieved, where we can share thoughts and worries and ideas with others we know, where we can collaborate and discuss common interests, and where we can contribute something back to the group and see its impact.

The urge for community is so strong that it has been encoded into the physical structure of the encampments, villages, towns, and cities that humans have built and inhabited for eons. Need to get a dose of community? Head to the campfire, the pub, the city square. There you can find a group of people to chat with, stand up to declaim your passion, tack something to the message post, discover that someone has a problem that you might help solve, create a society of the like-minded, or plan how you'll make your local mark and be remembered by your community.

That full, rich sense of membership in a community is deeply important and valuable to us. It can give us purpose and motivation, comfort and camaraderie. I would argue that civilization has been built from strong individual units of community, like societal bricks, and when those bricks begin to dissolve, the structure tumbles down. (But that's a story for another day...)

Until around the 1980's, there was exactly one way to get that full community experience: in person. Your community was made of the people you could touch.

The BBS was, I believe, the first technology in history that made it possible to get some form of true fully-formed community between physically separated people. It offered all the elements of community that had always been provided exclusively by local in-person groups, clubs, meetings, parties, pubs, and town squares.

(If you're interested, you can get a feel for what they were like here...)

If you knew what was up, the BBS wasn't just digital correspondence, it was the embryonic form of community in cyberspace, man. It was the stuff of sci-fi, where human stories could play out in a purely digital "place" between digital avatars of all description, controlled by people sitting in darkened rooms around the world. We joked about the cliches of being "jacked in", but it was undeniably cool.

An Accidental Prototype for Digital Community

The BBS I spent by far most of my time on was called (not kidding) Cyberverse.

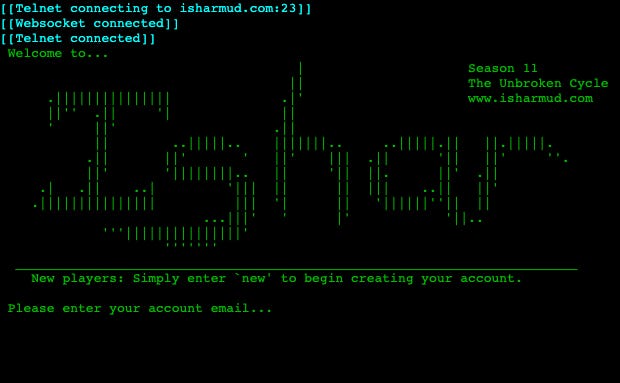

Cyberverse had all of the typical BBS features, but also a special one: it had a MUD. I won't even explain what MUD stands for, but the basic idea is that it's like an MMORPG, but instead of graphics, it's 100% prose – text, like a first-person fantasy novel, describing what you're "looking at" and what you're "doing" (by typing). It was like ZORK but rather than a world frozen on a floppy disk for a single player, it was a shared virtual space for many players to explore and hang out in together.

The particular MUD running on Cyberverse was one built and written from scratch called Ishar.

Ishar's world translated all of the physical features of a real (that is, magical fantasy) medieval world into the digital. Its main town had a central plaza that people would pop into like the local pub, message boards with the latest topics of discussion and drama, and all sorts of places to not just battle creatures but generally hang out with other people. It included commands called "socials" – canned phrases conveying all the sorts of non-verbal messages we take for granted in reality, like a more literary version of emojis. Ishar was even was designed so that particularly creative players could add to the world itself from within.

With a players base measured in dozens, you became known (by your handle) for your deeds and personality and fell into one or another social group there as you played and conversed. A genuinely new player was a noteworthy event – How did you find us? Where are you from? Need any help getting started?

It was awesome. When I was 16, awkwardly exploring social connections and finding my place, Cyberverse and Ishar suddenly expanded the scope of my world, out of my local neighborhood and into the virtual. Despite being text in a terminal window, it immediately felt more full of potential than the physical forms of community I had access to. Ishar sunk into my brain instantly like a drug – as it did for others who also grew up in the disconnected world but were now eagerly exploring virtual ones.

I added to my friends a set of people scattered around greater Los Angeles and my modem stayed dialed in for most evenings and weekends as I hung out with them in a world built of hackishly enthusiastic fantasy prose. Once we had mostly played through the fantasy game that was the notional purpose of Ishar, we took up residence and stayed there anyway because it was simply a great "place" to be, accessible 24/7 from any computer terminal.

From time to time, there would be a "MUD meet" where people would get together physically to hang out. Those gatherings had a strange flatness; they seemed almost unnecessary when we were constantly hanging out virtually anyway, and out here in meatspace we didn't even have the magical powers and convenient tools that we were used to. Usually the meets ended with us finding computer terminals to sit down at, to find out what was going on in the real community in the virtual world.

We took it as a given that Ishar was a prototype of the future – a future of digital community. Of course new technology would eventually make all information available instantly at our fingertips, but that wasn't even the best part. Digital community was a concept that could expand to remake how the people around the world connected with each other, without restrictions.

As more people got online, we expected virtual worlds to grow and expand and become ever more rich and compelling. Of course local physical community would remain important, but we would each also find new communities within the vast electronic realm, like citizens of a metropolis of billions. Us Isharians were already inhabiting a virtual place that, even in crude and highly imperfect form, enabled real community without the hard limits of physical separation that had held since the beginning of time.

(Ishar still exists, by the way, connected to the internet. A community lives on there – with none of the original members, but retaining a continuity of community encoded in the digital world and its history and lore. It's a testament to the draw of community, even when the mechanism has become incredibly outdated.)

Opening of the Internet's Wild West

It was around this time that Cyberverse added a new thing for us users to do: the Internet.

Initially, "the Internet" was literally a menu option within the Cyberverse BBS interface, giving access to various internet protocols that did very specific things. In many ways, it still felt like a global expansion of the BBS experience and its various functions. Early internet software protocols provided individually useful concepts like sending mail (Email), serving collections of files (FTP, Archie, Gopher), live chat (talk, IRC), and posting of messages to topical groups (Usenet). After choosing a given protocol, you could type in the addresses of servers around the world, and see what they had to offer.

It was undoubtedly clunky, but back then it was hard to envision what the "right" way to make use of the internet was. The capability of the network itself was mind-blowing: instant, global communication, to be used however you see fit! But it was like giving steam-age engineers access to a nuclear power plant with bare electrical terminals mounted on the outside... what sort of thing even makes sense to build and connect to this immense power?

Nonetheless, despite the clunkiness (maybe even because of it for a tech-head), the sudden extension of reach was heady for us Cyberverse users. Now our bubble wasn't just weirdos around Los Angeles, it was weirdos (and a bunch of universities) around the world. Places on the other side of the planet ceased to be abstractions seen on the TV news, but places holding real people we could talk to and trade files with, instantly.

Even at this point in the mid-90s, there were millions of people online from distant places, but it still felt a bit like a small community. To start, there were still a lot of natural commonalities between the kinds of people who managed to get online then. And, like the lists of BBS phone numbers that got around, you managed to find groups of people on various usenet groups, mailing lists, and IRC channels where you could get that feeling of membership in a community that wasn't too big to get to know you. The interface sometimes felt a little disappointing to us Ishar users, but the global scope was worth the tradeoff.

So in 1995 or so, it still seemed to everyone that virtual community would be a big part of what we would do with the raw capability the internet gave us. A modem company even called themselves Global Village, echoing the vibe of the times: we were on the verge of a predicted transition to a more personal world! The more wide-eyed folks imagined that, like in cyberpunk novels, everything could happen within an immersive simulated 3D world where you would interact with people, systems, and information "physically". A few tenuous attempts were even made in that direction, like GopherVR which attempted to represent a network of servers and documents in a 3D environment.

The Internet Becomes the Web

Despite the raw capabilities of the early internet protocols, ease of use is always king. A proliferation of separate protocols, each with their own unique software to learn, was confusing and burdensome (and it was vastly premature to try for a VR-style physical UI paradigm – 30 years later it still doesn't quite make sense). The way forward was convenience, and that meant putting everything into a window with a simple, unified point-and-click interface.

The protocol that figured it out was HTTP – the basis of the World Wide Web – with its paradigm of a "browser" and living documents that could be connected to each other in a web of information.

Across 30 years, HTTP has become the primary unified protocol behind the huge variety of websites, services, and apps that we think of as "the internet". It works so well in large part because the "webpage" concept is so flexible. It isn't like the old protocols designed for a very specific and narrow function. HTTP makes it simple to make generic requests for data, making it easy for a developer to adapt it to their own purposes with their own user interfaces. Initially the user interfaces were simple HTML pages, but the underlying protocol was easily extended almost endlessly.

So when the Web came along, the energy drained from the proliferation of specialized protocols. The protocol question was now settled, and the real exploration of how the internet would remake the world got started in earnest. We headed into successive waves of exploration and development: the dot-com gold rush to put everything on the web, the user content generation push of Web 2.0, the rise of smartphones and the app-ification of everything, and finally the dominance of pervasive social media.

Finding my global community would be on the web, but it didn’t go how I expected.

Click here to go on to part 2, where I pick up the story of the web taking over everything, social media swallowing how we socialize online, and how an illusion of community is actually pushing us apart.