The Cyberpunk Primer

A starting point for the books, films, TV, comics, and games that inhabit the techno-noir dystopias we feared (and welcomed) in the 80s ... and probably live in today.

I love cyberpunk.

I grew up in just the right place and time for cyberpunk's peak 80s-and-early-90s era to feel both plausibly prescient and totally rad. I had my hands on the embryonic forms of virtual reality that would get us there, and the Asia-inflected hyper-commercialized megacity concept seemed like a plausible direction Los Angeles could go given the right economic conditions (and maybe even felt like a welcome alternative to the dusty decay of 1980s LA).

Right here and now in 2025 – 6 years after the setting of Blade Runner – cyberpunk also provides a bracingly relevant framework for understanding our current world. We live in a reality of trillion-dollar transnational tech companies, AI technology that's cutting a swath through society like a pandemic, massive wealth disparities between the working class and the unimaginably wealthy, pervasive mass corporate surveillance, millions doing app-managed gig work, decentralized cryptocurrencies, government-backed hacker groups disrupting critical infrastructure and elections, and the population of the world essentially jacked into a shared infosphere 24/7.

For those getting started with the genre, I wanted to provide a primer and some entry points to understand what cyberpunk has to say and the kinds of worlds you can explore there, including a list of some of the works I think are the greatest and most influential.

So consider this article a dingy data stick, pressed into your palm in a dark alley – just out of holo-drone scan range – by an old sallow-cheeked netrunner with an outdated neural interface blinking at his temple. "I've seen things..." he mutters. "That is just a sample... I'll be here if you want more."

Cyberpunk Origins

Before I get to the list of media to plug into your brain first, let me define what defines "cyberpunk" that lives up to the name, starting with a little history.

Cyberpunk is a genre that could never be described as "timeless". Its unique combination of immersive future-shock excitement and techno-capitalist dystopian fear arose from a specific combination of late 20th century optimism and paranoia. It's a feeling that sizzled in the collective subconscious as we watched technology begin to remake the world at an accelerating pace.

The stories that first emerged from those fears and desires naturally looked fixedly forward. The foundations of the genre were laid by stories that imagined the dark side of what the world might become if unrestrained profit-driven technology development continued on its rising arc of dominance. What would it be like to live in that world, as the individual becomes insignificant and the line between human and technology begins to blur?

As the 1980s began, a dark future felt increasingly just around the corner (20 minutes into the future as one put it) and cyberpunk had found its moment. The genre rapidly built up a consensual hallucination of the cyberpunk future as writers, directors, and artists caught the mind virus and contributed their own take.

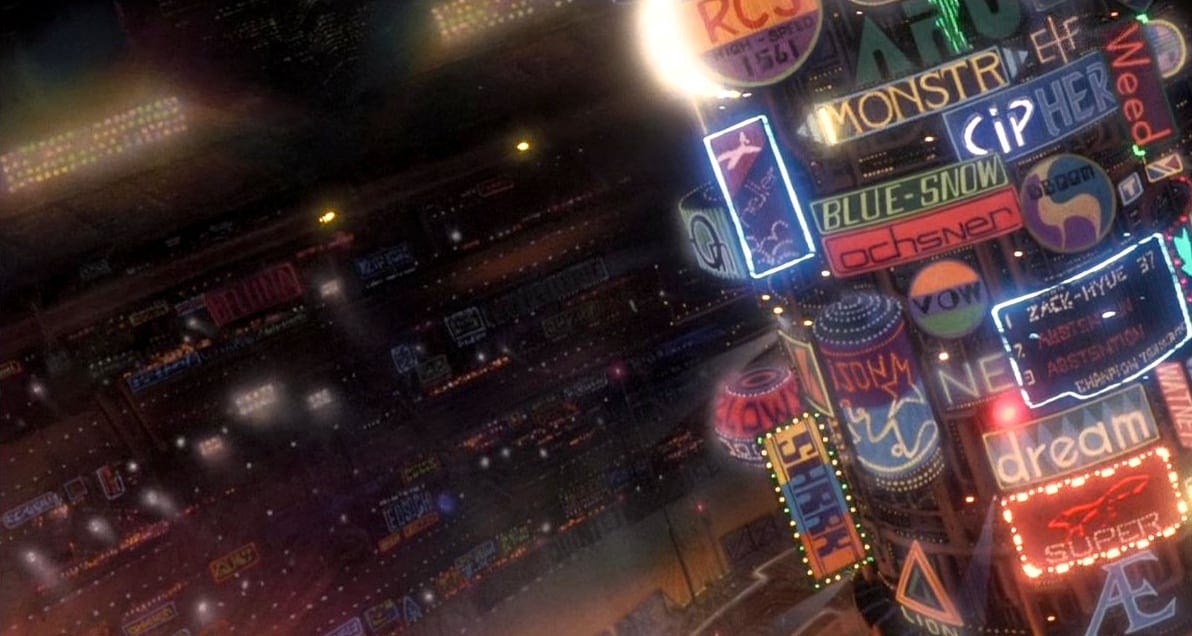

A common aesthetic emerged; it was a wild and sinister extrapolation of 80's greed-is-good economics, fast-moving technology, Japan at the height of its electronics and manufacturing dominance, and anarchist counterculture. The cyberpunk world sharpened into neon-lit focus with looming megacorps, inescapable advertising, chunky electromechanical cyber-tech, and a tech-savvy gutter-punk attitude for those living at the fringes.

Then something funny happened around the mid 90s: the tech outpaced the genre.

When the combined revolutions of the internet and personal computing took off, cyberpunk's paranoia and excitement might have seemed all the more justified and immediate, but the aesthetics of the future took a hard left turn and pulled away at full throttle. Moving into the early 2000s, brain interfaces seemed more distant, but internet technology blew past what anybody expected. The form of high tech redirected away from button-and-light encrusted devices, toward being connected, software-defined, touchscreen-enabled, embedded, and wireless – in short: invisible.

Now, out here in the far future of 2025 (6 years after Blade Runner's setting), we live in a a cyberpunk world stripped of the visual cues we expected. The true techno-corporate dystopia turned out to be clean, convenient, brightly-lit, and personalized. The brain interface we got was a rectangle of glass in our pockets.

Cyberpunk Endures

Despite its distinctly 80s origins, Cyberpunk has lived on. The genre has continued to tell stories that are all the more relevant, but often still wrapped in aesthetics that are now decidedly retro.

Because if that world was so engaging, why give it up as a place to tell stories that still have impact? In retrospect, it was always absurd to think that technology capable of futuristic miracles like mind-computer interfaces would look like the chunky electronic devices of the 80s (plus more cabling), and that cities would drift toward a fever dream version of 80s Hong Kong. But it's unquestionably cool.

Ironically, cyberpunk's world concept is no less fantastical than cyberpunk's awkward spin-offs like steampunk, which imagines futuristic miracles emerging from 19th century mechanical technology taken to dark extremes with the brass-and-oak British empire aesthetics. Who cares if it's implausible if it's a fun place to be? Star Wars has always played a similar trick, imagining far-flung future miracles that are riveted together like WWII bombers and and wired up like radio kits – ridiculous, but an evocative conceit for telling stories of a Nazi-Germany-like expansionist empire and a plucky resistance.

So Cyberpunk – even the unashamedly 80s-inflected variety – remains a genre worth returning to, whether for thoughtful stories about where we're headed as a society and species, or gonzo pulp noir tales that we can't put down. Maybe it is timeless after all, if we understand what makes it enduringly special.

Cyberpunk is sometimes treated as simply shorthand for "sci-fi dystopia", but I think it deserves a more specific definition. The Incal or Judge Dredd comics are great dystopian sci-fi (and highly influential in imagining sci-fi megacities), but I wouldn't quite call it cyberpunk because they focus more on the fantasticality of the world or themes of authoritarianism, rather than the sort of capitalism-driven class struggle and technology-driven redefinition of what it means to be human that gives cyberpunk weight.

I also think it's hard to call something cyberpunk if it doesn't have a pretty tangible link to our current world – a feeling that plausibly this dystopia might be lurking right around the corner. So as much as I love sci-fi works like Schismatrix or Quantum Thief that feature brilliant elements of post-humanism and even some punk ethos, their wild far future sci-fi worlds are too far separated from our own to deliver cyberpunk's visceral grit and paranoia.

So I'd say that cyberpunk has three absolutely essential elements:

A world dominated by exploitative mega-corporations controlling high technology

Technology that calls into question the nature of humanity and/or reality

Massive economic inequality and violent class warfare as a result

The first gives the genre immediacy and relevance. The second gives you the cyber. The third gives you the punk. (And no wonder that there is a natural affinity with the noir genre: the big city, haves and have-nots, and a crime that links them.)

Building on those essential foundations, cyberpunk has collected a set of common building blocks that often contributes to a work's cyberpunkness:

Virtual reality

Androids and technologically augmented humans

Artificial intelligence

Technological singularities, with unpredictable runaway results

Hyper-dense architecture, with the haves at the rarified top and have-nots at the filthy bottom

Advertising run amok, lighting up the city in unnatural hues through the night

So using this as a guide, here are some of the greatest and most influential cyberpunk works across media, split into three eras of the genre's development (plus some extras at the end).

Cyberpunk Forerunners

A few key works ahead of cyberpunk's time that did it first and set the stage.

Metropolis (film, 1927, Fritz Lang)

Stop and appreciate just how ahead of its time this movie was. In the 1920s, the most bleeding-edge experimental technology was television. Electronics would be based on vacuum tubes for decades to come. Films, including this one, were still silent.

And yet Fritz Lang leaps straight to imagining a future of skyscraper-studded megacities, run by a corporate elite, supported by a workforce dehumanized by automation, and an android clone of a working class hero used to manipulate the opinion of the masses. You can draw a straight line from the mad scientist Rotwang to Blade Runner's corporate CEO Eldon Tyrell. Cyberpunk starts here.

Ubik (novel, 1969, Philip K. Dick)

Dick also famously wrote Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep which (loosely) inspired Blade Runner, but for my money, Ubik delivers the better 60s proto-cyberpunk vision. Taking corporate dominance as a given, the world of Ubik is hyper-consumerized: everything used by the working class is coin-operated and “Ubik” itself is a marketing brand-name of shifting meaning. The protagonist is caught helpless in a struggle between corporate interests, and his reality begins to come apart at the seams. Explanations are elusive, but my read is that it's maybe the first novel that takes place in a form of virtual reality, all related to a mysterious technology represented by “Ubik”.

(Safe when taken as directed.)

The Girl Who Was Plugged In (novella, 1974, James Tiptree Jr.)

I will forever maintain that this criminally under-appreciated novella truly invented fully-formed cyberpunk and was the secret inspiration of the greats that followed. I discovered this long after reading through the cyberpunk canon and my jaw was on the floor. It has just about every element of story, tech, and aesthetic – in 1974 – that we would come to know as cyberpunk, and it's got the attitude locked down. Just read this opener:

Listen, zombie. Believe me. What I could tell you—you with your silly hands leaking sweat on your growth-stocks portfolio. One-ten lousy hacks of AT&T on twentypoint margin and you think you’re Evel Knievel. AT&T? You doubleknit dummy, how I’d love to show you something. Look, dead daddy, I’d say. See for instance that rotten girl? In the crowd over there, that one gaping at her gods. One rotten girl in the city of the future. (That’s what I said.) Watch.

Fucking cyberpunk. Swap AT&T and Evel Knievel for Nvidia and Travis Pastrana and you could publish that today.

Maybe the only thing The Girl... lacks is the lone hacker knocking around in cyberspace, encountering an emergent AI. Which brings us on to...

True Names (novella, 1981, Vernor Vinge)

Incredibly influential, Vinge's True Names establishes the modern notion of virtual reality – a shared global digital 3D space inhabited by avatars controlled by users. From that launching off point, he tells a story of wily hackers who get drawn into very deep virtual waters with powerful forces, and a conflict that has devastating effect on the real world.

After True Names, every writer had a concrete vision implanted in their minds of brain-computer interfaces, runaway technology, and the rapidly-approaching potential for humans to become something more.

Cyberpunk Peak Era

This is the time where all the pieces were in place for an explosion of cyberpunk output that felt just in time to understand, and be properly excited by/terrified of, the world we were about to create in the 80s and 90s. These are the works that achieved the highest highs for me, and it kicks off with a spectacular 1982 ...

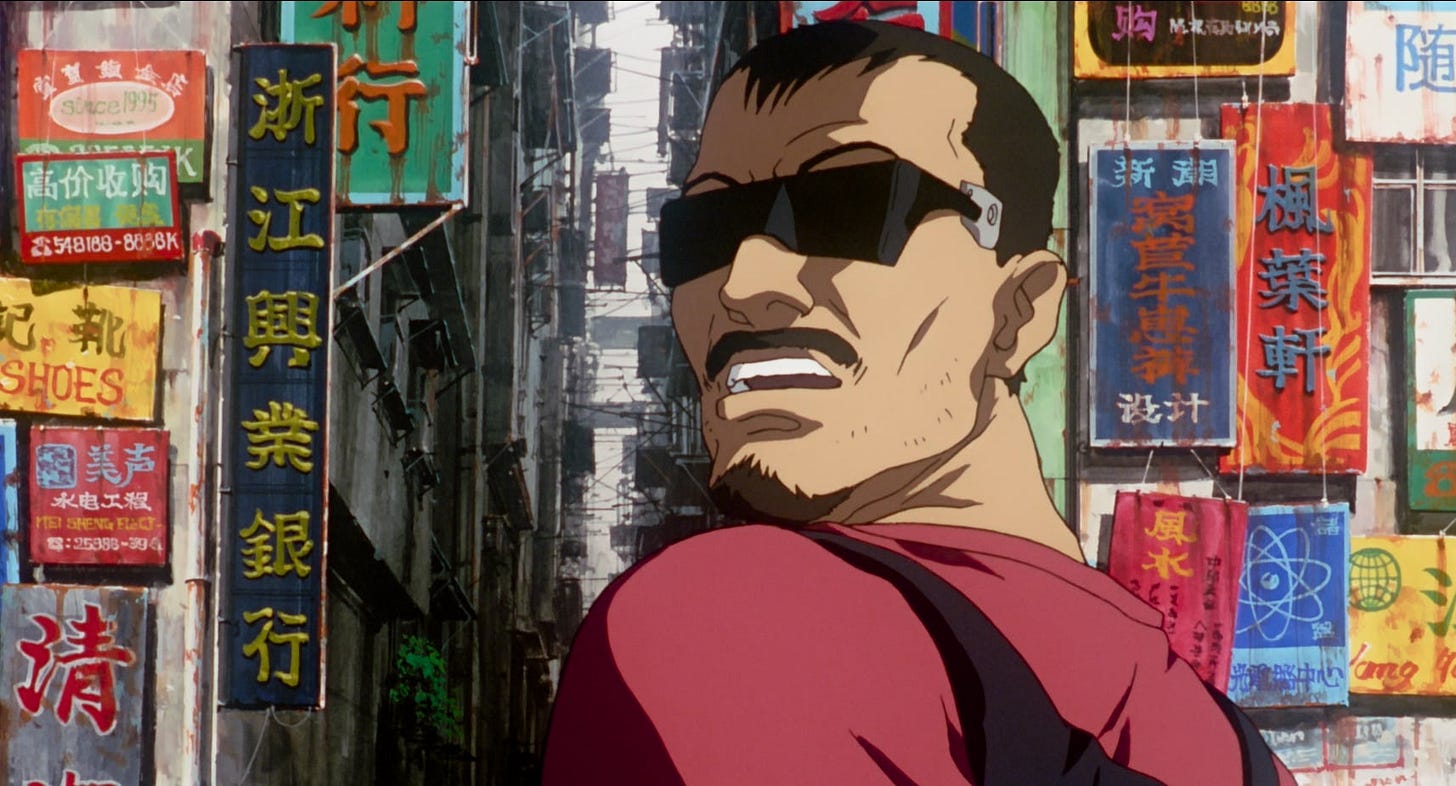

Akira (manga, 1982, Katsuhiro Otomo)

No place on earth was riding the technological wave of the 80s harder and faster than Japan, and cyberpunk found a natural home there. Akira provided a feverishly imagined cyberpunk Tokyo overrun with technology like an invasive organism and a terrifying vision of corporate trans-humanism. It also established that the best cyberpunk protagonist is one from the slums with a high-tech motorcycle. The later film version is excellent, but nothing beats staring at the full-page spreads of the original manga.

Blade Runner (film, 1982, Ridley Scott)

In the same year as Akira, Blade Runner provided another aesthetically definitive cyberpunk vision. Syd Mead's design work on the film flipped the optimism of his prior (often corporate-funded) futurism on its head to create a bleakly failed techno-Los Angeles. Blade Runner, and its private dick android hunter, was perhaps the first work to recognize that you can map a straight noir tale directly onto cyberpunk and the result is beautiful.

Tron (film, 1982, Steven Lisberger)

Maybe a controversial pick. But my god, Disney released this in 1982? As groundbreaking as Akira and Blade Runner were during the same year, Tron was the first popular imagining of virtual reality as the battleground between the little guy and the corpo overlords (and their sinister AI). There's a weird kind of cyberpunk trinity here, linked by Syd Mead's Tron lightbike design – a crisp virtual object compared with the real-world grime of Mead's LA in Blade Runner, and an iconic motorcycle design that inspired the design of Kaneda's bike in Akira.

Neuromancer (novel, 1984, William Gibson)

Often cited as the seminal cyberpunk novel, Gibson puts all the pieces together: cyberspace, megacorps, hackers, noir, AI, Japan, digitized consciousness ... and throws in ninajs, mirror shades, razor fingernails, an orbital enclave for the wealthy, and a bunch of hip cyber-jargon that would end up sticking with the genre forever. Gibson has always been more of an observer of social phenomenon than a tech-head, but those have often ended up being the aspects of cyberpunk that have turned out to come true.

Robocop (film, 1987, Paul Verhoeven)

Maybe also a little controversial, but stay with me. While all the action in cyberpunk world is clearly happening around the Pacific rim (see above), I always wondered what was going on in the second-tier cities of the world. What about Detroit? OCP, ED-209, and Robocop – a man hybridized with tech for the profit of the local two-bit tech executives. It establishes the cyberpunk idea of the law enforcement protagonist who is almost as much a victim of corpo control as the suckers in the gutter.

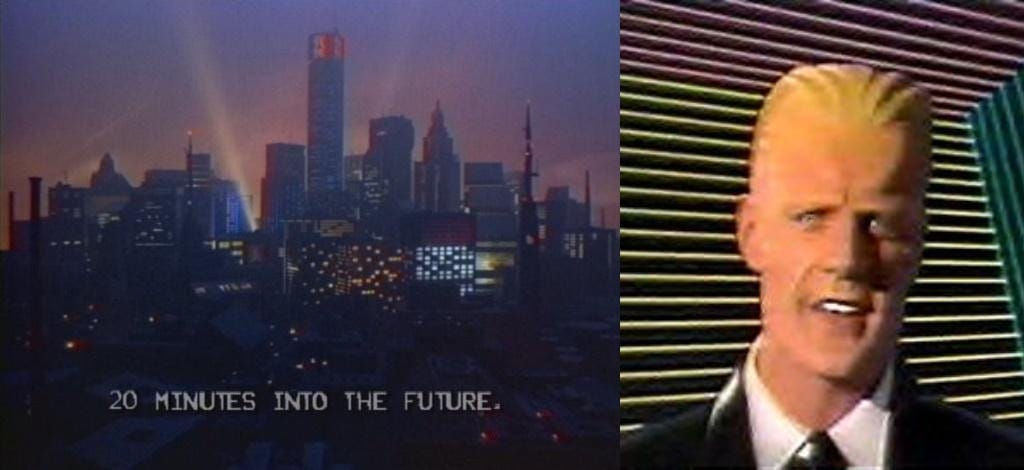

Max Headroom (TV series, 1987)

Max Headroom has the honor of bringing a thick slice of no-compromises cyberpunk to television for the first time, and it's fantastic. Its own spin on the formula is to fuse the powers of tech and media under a dark governing corporate broadcast entity Network 23. Here the protagonists are independent journalists. Admittedly it missed the mark pretty badly on what the internet would do to news and networks. But: it has cyberpunk vibes for days, imagines digitized consciousness as not ready for prime time in the form of the glitchy Max, and it starts with the genius tagline 20 minutes into the future...

Snow Crash (novel, 1992, Neal Stephenson)

As Neal Stephenson tends to do, with Snow Crash he got properly obsessed with some stuff – corporations controlling the future and hacking the brain among other things – and drove those ideas to their extreme endpoints. This isn't just a dark city with the logos of corporates on buildings in 50-foot neon, it's an America that has spun apart into city states and franchise-organized quasi-national entities. It's cyberpunk on eyeball-injected neuro-stims, contains lengthy diversions on Sumerian culture, and not only puts the lone hacker hero protagonist (named Hiro Protagonist) on a motorcycle, but straps a katana to his back. It was also famously influential among the internet boom generation of silicon valley tech elite, among other things coining the phrase "Metaverse".

Ghost in the Shell (film, 1995, Mamoru Oshii)

For me, this is the pinnacle – the culmination of the genre, and the final capstone to the era of cyberpunk without a trace of irony. It picks up the thread of the augmented law enforcement officer, embraces the best cyberpunk elements of what came before, and weaves it all into a contemplation on the nature of conscious existence with flawless animated action across the highs and lows of its Hong Kong-inspired future city. Without it, The Matrix would not exist.

It could only have been made in the mid-90s; just late enough that the internet is a core part of the world (in a way that maybe only True Names foresaw), but early enough that the possibilities of the internet were formless, leaving room for Ghost in the Shell to fill up the imagination with a gorgeous and maybe-just-plausible cyberpunk world.

Cyberpunk Retrovibes Era

Heading into the end of the 90s and beyond, the cyberpunk aesthetic had dated itself and cyberpunk lost much of its literary steam. But it became a productive wellspring for film, TV, and video games for a certain kind of often irony-tinged nostalgia – an alt-future that might have been. A spate of truly terrible, lazy cyberpunk, VR, and hacker films did their best to kill the genre, but the good stuff has kept the flame alive.

Deus Ex (video game, 2000)

This wasn't the first cyberpunk video game by any means, but it was a superb achievement. It eagerly and lovingly put its arms around virtually every trope of the genre, and had the brilliant insight of adding conspiracy theory paranoia to the mix. Still worth playing 25 years later.

Altered Carbon (novel, 2002, Richard K. Morgan)

Similar to Deus Ex, Altered Carbon fully commits to the bit. It's every inch the pulpiest of pulp noir stories, told through a thick pastiche of timeworn cyberpunk tropes. There are no deep insights to be had here, but it's a hell of a joyride.

Ghost in the Shell: Standalone Complex (TV series, 2002)

This series is kind of related to the original 1995 movie, but is more of an alternate reality story than a sequel. It's a police procedural at its core that still very much inhabits the sort of cyberpunk world we saw in the film. The episodic format gives it a lot more room to explore the corners of that world and tell individual stories about augmented humanity, tech-enabled control and rebellion, and AI – as well as a longer-arc about emergent social phenomena in an incomprehensibly complex and interconnected world. It's fantastic TV, and I’ll take my dystopia with a tachikoma companion.

Psycho-Pass (TV series + films, 2012)

Made by the same studio as Standalone Complex, it almost feels like a prequel to that show, with things like cyberbrains and pervasive androids just on the horizon. Again a police procedural, it focuses more on surveillance, control, and power – and crucially the kind of people who come to wield it. It really hit its stride with the movie Sinners of the System which steps outside the typical Neotokyo city center to explore what we might expect in a wider cyberpunk global setting.

Mr. Robot (TV series, 2015, Sam Esmail)

The brilliant thing about Mr. Robot is that it's a fully committed oldskool cyberpunk hacker-vs-corpo story with all the beats you'd expect, but played absolutely straight in its setting in our current day, rather than a gritty cybercity. The insight here is that we already live in a cyberpunk dystopia, but without the neon-drenched trappings. And Mr. Robot gets extra points for being nearly as technically accurate in its depiction of real hacking techniques as you could expect from popular entertainment. The first season and (frustratingly) the last season are especially great.

And More...

While not trying to create anything like a comprehensive list of cyberpunk works, here are a few extra items worthy of a scan.

Neo Tokyo (film, 1987)

This anthology of 3 short films is a satisfying meal if hungry for more Japanese-inflected cyberpunk world building.

Shadowrun (tabletop game, 1989)

Not satisfied to just be a well-designed cyberpunk D&D style game, Shadowrun adds a magical fantasy element into the mix which is oddly compelling. The much more recent video games are pretty solid as well.

Blame! (manga, 1997)

This nearly violates cyberpunk requirements by being set in a far distant future, but I give it a pass because it's a future firmly rooted in a recognizably near-future cyberpunk world. Imagine the worlds above, and then let the forces of those worlds run wild for tens of thousands of years. Then begin your journey with a boy and a gun, trudging through the ruins.

Rainbow's End (novel, 2006, Vernor Vinge)

Sadly Vinge's last novel, Rainbow's End explores cyberpunk concepts stripped of the outdated aesthetic baggage and updated for the arc technology actually took in the intervening years since his True Names. Told mostly from the point of view of children who have grown up with elaborate augmented reality technology, it's a very different take.

Deus Ex: Human Revolution (video game, 2011)

A worthy extension to the original Deus Ex, with a greater focus on biotech.

Quadrilateral Cowboy (video game, 2016)

A tiny indie game with hilariously lo-fi graphics, nothing else has made me feel more like the elite hacker in a cyberpunk crew.

Cyberpunk 2077 (video game, 2020)

You gotta respect the dedication to crafting a deep and high-fidelity, while decidedly oldskool, cyberpunk experience.

Pantheon (TV series, 2022)

Based on set of short stories by Ken Liu. Like Mr. Robot, Pantheon sets aside the 80s aesthetics of typical cyberpunk, starting in a very familiar world – perhaps just a few years ahead of us. It imagines the tipping point when one of our current silicon valley mega-corps reaches a critical threshold of computing capacity, neural algorithms, and biotech and unstoppable forces remake the world as a distinctly trans-human cyberpunk place.

A quick addendum.

I realize The Matrix seems like a large omission from this list. Partially I left if off just because it doesn't particularly need more attention, and partially I've always been slightly put off by how much it's a direct pastiche of elements from previous cyberpunk, even if it gets some points for bringing it all to a mainstream audience.

I mention this just as context for a fun fact that puts a point on my opinion of The Matrix. If you watch episode 2 of Max Headroom (the American TV show version), you'll run into a character that is every inch Morpheus. Not in an "oh I guess he could have been an inspiration" way; it's just Morpheus.